Katharevousa and demotiki, or ‘wordways’ through the ivory-tower looking glass

By Jan Mahyuddin

Published: 23 Dec 2013 / Category: Fact /

The piece Noely wrote on December 12, ‘Does Australia hate intellectuals’, in response to Nick’s ‘Anti-Intellectualism – Does Australia Really Hate Thinkers?’, slipped past the plastering and painting and being an apprentice’s apprentice that’s been my renovating life in the last six weeks, and landed plumb in the mess of pottage that stands these days for my little grey cells.

Intellectuals. Academics. Language. Communication. Hate?

Can the little grey cells turn potted reno sludge into #thinkyness, is the question. (And by the way, this began as a comment, and then fell a long way down somebody’s rabbithole!)

Let’s see.

At the end of the seventies, I lost my job as a tutor (we also had responsibility for lecturing) at a regional university – because of funding cuts, but also because my nascent efforts at ‘publishing and perishing’ hadn’t been super successful. Some of us, no matter how lauded our undergraduate years, should never have tried, as postgraduates, to be ‘working the ivory tower’. (But some of my very best friends were, and are, academics .) Jobless, and on the requisite pilgrimage to a few of the ‘mother countries’ (UK, Germany), while perhaps looking for work with the BBC (no, truly) I stopped off in Athens to see a Greek friend – and stayed for two and a half years.

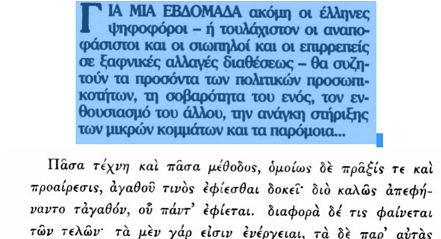

It was in Greece, as I struggled to learn some Greek (and am still struggling!), that I learned there were two forms of the modern Greek language, katharevousa and demotiki, that had vied to be the formal, recognised language of the Greek state. Demotiki is often defined as the idiomatic spoken language of the ‘lay people’ (and was made Greece’s official language in 1976). Katharevousa was a more formal, ‘pure’ and far more grammatically complex, as well as partly ‘reconstructed’, language of the educated, the wealthy, the elites - including governments and the army. Here were inside/outside/class/power memes to wrestle with – but not for the first time.

For the record, since that first lost job, my working life continued to slip both ways through the looking glass of the ivory tower, or in and out of the Australian academic universe, for the next 30 years, twice, at least in ‘academic positions’, although, as E. M. Forster might say (yes the lapsed doctorate was on his work – clever you ;-) ), these positions were ‘at a slight angle to the academic’s universe’. And for the record, my last professional position was back, after some 30 plus years, in the original regional university - but not in an academic position – until mid 2012, when I became a gypsy.

It was in the first stint at the first regional university that I fell over the discussion that seems never to go away: in those days, one academic friend, who believed passionately that Australia was very anti-intellectual, consistently framed the debate as ‘new thoughts need new language’. In her defence, she was a post-war immigrant growing up within the tradition of respect for the intellectual that remains current in Europe. ‘New thoughts need new language’ was her argument for writing and speaking the then theoretically ‘structuralist, post-structuralist’ language invading the humanities that read and sounded when spoken as if chewed through a mouthful of small metal pieces. (Yes, my bias against building ‘ugly’ language to serve evolving theory is showin’.) It was also her (and many other academics’) argument, and still is in many courses (such as the ‘thinky’ or ‘intellectual’ subjects that Nick refers to in his piece) that students must learn to work with the theoretical frameworks that underpin the discipline … and not baulk. This means learning the formal, evolved or constructed, but ‘closed’, language of the academic discipline to which they are seeking to be admitted.

You can pick, in a split second in the print media, op eds from a just-minted holder of a doctorate that began life as their chewy, metallic ‘katharevousa’. The good news is that some go on to find their ‘demotiki’, their language that speaks to and with the ‘ordinary punter’ (non-academic, non-specialised reader, listener, voter) just as well as Nick does, in spite of his reservations and honest self-examination of the difficulties in, and constraints on, doing so.

That we learn and use different languages in different contexts is no new thought. Noely picks an iconic one – sport – in her piece, by way of illustration. Many languages are bound firmly into the practices of institutions, even estates: governance, law, the academy, religious institutions, and so on. Of these, we may ever only learn a little, because they are essentially a form of katharevousa. Most of us will need a mediator some of the time to get to ‘demotic’ understanding, and I suspect no amount of plain English projects will do away with this need in any foreseeable future.

When Noely says:

We need more of a respect for science, academics, experts etc in the general public, from primary schooling onwards. Though, we also need these very same Intellectuals to actually learn to communicate.

and asks:

What is the point in accumulating all that knowledge if you don’t use it, share it, spread it further amongst the masses to encourage learning?

she is echoing precisely what I asked and argued about for some years with my ‘new thoughts/new language’ friend.

I have vivid memories of several – let’s call them ‘moments’, perhaps – in those times.

The first. My friend was invited onto Philip Adam’s ‘Late Night Live’ (in the late eighties). Although the project he wanted to talk about was cutting edge and relevant, and its worth readily translatable to the ‘common good’, she spoke the language of her discipline, her katharevousa. He spoke demotiki, trying to mediate ‘for the people’. She felt misunderstood, he gave up, and the interview ended quickly. Cosmos knows what ABC listeners made of it, but it was one early moment I felt truly sad about any possibility of bridging this kind of ‘language gap’.

The second. At the point at which I lost the tutoring job, my friend moved on to a lectureship at a predominantly ‘distance education’ university in Australia. Women Studies programs were fermenting all over the globe, and one was busily evolving at this university. Always generous in sharing her research and her work, my friend sent (snail mail then) copies of course notes with an especially drawn program cartoon adorning the covers. The cartoon? A cleaning woman with a pinny and turbany scarf was sweeping up words in the empty lecture theatre, all the ‘big’ ones sifting out from the burgeoning theories that underpinned and shaped the ‘new discipline’ of ‘studying women’. Concerned (late seventies) that Australians could be ‘anti-intellectual’ the academic staff committed to this program assumed their new students could be, too. But in their attempt to pre-empt and even reassure, the staff had approved and used a cartoon stereotype that put down one group of ‘sisters’ in order to ‘privilege’ another. Classism, via ‘visual’ language. But, it’s also worth saying – no matter how noble the intent, when we’re on the rabbit-hole side of the looking glass, it’s very difficult to look at oneself as if one were … a person on the other side, on the outside, looking in.

The third ‘moment’ occurred when an Australian publisher suggested my friend edit an anthology of writing (relevant to my friend’s research interests and course development/teaching practice). Since my friend wanted the anthology to become a useful text for higher/tertiary ed., and also for secondary education, and since I was then working on the other, not rabbit-hole, side of the looking glass (with TAFE), she asked me to co-edit, with the expectation that my outside-the-ivory-tower ‘position’ might mean we could pitch the text to more than one demographic and market. Didn’t work it through at the time, even though this was post ‘the Greece experience’, but she saw ‘me’ as demotiki, mediating the katharevousa.

Mark Fletcher (blogging at Only the Sangfroid) in a post on Nick’s piece on anti-intellectualism makes the following point about academics joining the public debate:

I don’t think the answer is for greater participation of academics in the public debate. Think tanks are — in theory — supposed to be translating research into policy material for debate. They are failing at that task. And opinion writers are supposed to be taking the agreed facts and developing appropriate language for debate. They are failing at that task. We shouldn’t expect academics to plug the gap caused by the failures of others.

In other words, they shouldn’t. Are they being protected, or constrained, from having to speak in anything other than their own special tongue?

Must they have mediators through the looking glass?

London to a brick the Dr Karls of the academy (Dr Karl is, indeed, a Fellow of the Sydney Uni Physics Dept, so yes, the academy) don’t need, or look for, anyone to mediate: they leapt out of the rabbit hole, shattering the looking glass, long ago, while wooing us lay citizens all, as Noely points out, in perfect demotiki.

And it’s no coincidence that within the ivory tower in the last twenty years we’ve seen the rise of ‘career paths’ and ‘rewards’ for effective academic teaching, for those Dr Karls who don’t look outside the university, but make their students their public. Once, whether you were a brilliant teacher or not, if your research wasn’t considered sufficient or sound, because only your research was valued, you were shoved sideways into ‘administration’ and, not to mention, derided.

And who are the ‘opinion writers’ Mark sees as those mediators for the academy?

Journalists, who were trained in and dedicated to the fields and disciplines academics researched and published in and were brilliant translators of research for lay understanding? Journalists, now, who in the last few years have been eliminated from the staff of organisations such as Fairfax and News Ltd? Journalists, now, who take to Twitter to a) source content, or b) fight a last, already lost battle to keep the ravening tweeting hordes out of their own, once very specialised rabbit holes?

Journalism is undergoing huge change. And so is academe, albeit more slowly perhaps.

So far, none of this addresses Noely’s questioning of why it can be so difficult to engage with the intellectual, the ‘academic’ at the party (or on Twitter) who can’t operate linguistically, socially, behaviourally outside of their own constructed, but wholly real, world.

Seems to me that some ‘intellectuals’ will have been born never being able to learn demotiki – so I reckon it’s - have compassion, give up on ever trying to enter the head of a pure mathematician (unless we are one), and find someone else to chat up at the social event.

Some have demotiki thrust upon them (more and more by the institution these days), and seem to resent playing; these more than likely have ‘privileged’ their own intellectual and social position and assume there will be automatic deference (always the professor and never the ‘prof’); these may be people who put down the Twitter ‘outsider’ who doesn’t know the language and the manners and the mores of not only the given discipline or field, but of the ivory tower itself. Stay away. It’s not your fault; it’s theirs. And I’ve worked over my many years (as both academic colleague and as support staff) with a few.

Some, like Nick and Paul, achieve the blissful state of speaking/writing demotiki (beautifully :-) ) – whether just because they want to; or whether because they were born to and they couldn’t operate any other way; or whether because a changing ivory tower more and more demands a scholar do so now.

It’s not possible to think through all this stuff without realising that everyone in a society brings preconceptions, carries baggage based on past experiences and assumptions, about designated social roles -- and on how we ‘should’ interact with people in such roles. (When teaching in Greece in the early eighties, I was almost shocked to find the ‘respect’ automatically accorded to the ‘teacher’ in the community, not just by students, but by parents – and whether or not the teacher, as person, deserved such respect. Unaccustomed to this, I tried to break it down and challenge the students to think critically and question, but the absolute rigidity of expected behaviour towards the role itself meant that I could have taught them up was down and vice versa, and no-one in that community, then, would have questioned me.) Our own preconceptions can really trip us up, sometimes.

In 2011/12 and in my last full-time professional position back at the regional uni where I lost my first job, I was ‘brought in’ to provide support to students, and staff, in delivering a particular uni program – a distance delivery program. Partly online, it was decided to make the distance program fully so (aspects of designing ‘online education’ had become ‘my’ field over time). Both the program and the students are significant in this anecdote. The program is a tertiary entrance one – almost all Aussie unis have them now – where people who didn’t complete secondary school can take an entrance course, and these days, if successful, achieve an ATAR sufficient to enter their chosen degree. This program, though, was there when I taught within the now long-gone degree program thirty years ago, and is still there, thirty plus years later. Only the age-grouping has changed. Thirty years ago those tertiary entrance students averaged 40 to 70 years plus. Now they average 18 to 35 and are mainly young women, predominantly with children, often parenting alone, who want to make a difference in their lives. Now, though, as thirty years ago, every one of those students struggled with whether they should be there or not, whether they were ‘worthy’ or not, whether they belonged or not, whether they could do it, or not. I’ve never seen academic staff work so hard to find their inner demotiki, and build the confidence of so many of those wonderful, scared-shitless, mature-age young students, helping them to realise that they really did belong ‘through the ivory-tower looking glass’ and could overhaul their own preconceptions of what a successful university student might be, and what languages they were, after all, allowed to speak.

Last anecdote: it’s not only ordinary punters and late-entering students who can struggle with contexts intellectual and academic. During my time in the Arts Faculty at another regional university, a good many ‘professions’ were coming on board that had had no academic tradition in their training/learning/skilling approach: Social Work; Policing; Public Relations; Journalism. Those recruited as lecturers, as academics indeed, had never taught before other than maybe to run the occasional in-house training workshop. Some came on board with just as much fear, almost, about what life in a university required as a mature-age student might have, but rapidly became some of the most open and engaged and effective ‘teachers’, as well as productive researchers, that I’ve ever had the pleasure to work beside.

I like to think it was partly because they already lived in demotiki, and could so easily bring it, from outside the looking glass, straight through into the ivory tower. :-)

Social Media:

Spreading the word

- Please show your appreciation by following and supporting @lynlinking who works very hard to disseminate both blog posts & relevant media reports on a daily basis :)

Latest Thoughts

Latest Comments

What we are reading

About Us

Thinkyness came about from the charming @Perorationer who often tweets Jan & Noely in the morning with a random article he has found that would make you think, could be anything from Women in the 1800's to a potential world wide wine shortage which we would then discuss, obviously this led on to us tweeting each other #Thinkyness articles [...] more

Site Disclaimer

All articles displayed on this website are the personal opinion of the writers and do not reflect the official position of any businesses or organisations any writers may be associated with.